As countries around the world agree on targets for reducing fossil fuel use in an effort to slow global warming, a new renewable energy industry is thriving, driven largely by electric vehicles and targets for replacing coal oil and gas with solar and other energy sources. But this so-called “green” energy revolution comes at a cost that is borne mainly by communities far from the countries that are enjoying the benefits of the boom in renewables.

Solar panels and batteries for solar arrays and electric vehicles require metals that are found in various countries, not all of them traditional mining countries. Mining is a dirty business with a large environmental footprint, which often occurs in remote areas inhabited by Indigenous or other traditional peoples. And while the energy to which they contribute may be renewable, the minerals themselves are not, leading some critics to argue that the renewable energy boom is simply trading one unsustainable form of production for another.

Researchers and the industry are trying to compensate, calling for more recycling and reuse of minerals, as well as technologies that rely on more readily available materials with smaller environmental impacts. But those efforts are outpaced by the demand for minerals like lithium, which are considered “critical” for the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Ethicists are also divided, with some arguing that the urgency of the risk of runaway warming requires trade-offs while renewable energy technology catches up, while others call for a drastic reduction in energy use to decrease the need for more mining.

In Latin American countries, including Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, Mexico and Peru, governments seek to cash in on the demand for minerals that have not been mined traditionally in the region. They move on an economic chessboard dominated by the United States and China, which are competitors in the race to secure strategic minerals, and Russia, whose war on Ukraine has disrupted energy supplies to Europe, pushing the European Union toward a faster transition.

Caught in the middle are local communities, many of them Indigenous, where residents worry about harm to their land, draining of their water supplies and destruction of mountains they consider sacred. Experts say the looming challenges call for better governance, both in resource-rich countries and in the nations that are benefiting more quickly from the energy transition. But there is still far to go to level the playing field — if, indeed, that can be done.

Energy transition linked to pollution

For Marcos Orellana, both climate change and environmental contamination are human rights problems, and a just transition from fossil fuels to other sources of energy requires that they be addressed together. Orellana, who is the United Nations special rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes, put the issue before that multinational body in September, in a report to the 54th session of the UN Human Rights Commission. Both climate change and pollution are human rights

“The argument that we’re facing a global climate crisis and we need technologies that enable us to address that crisis regardless of the environmental cost or the pollution they cause is a false narrative,” Orellana told InquireFirst, “because we cannot solve the problem of climate change by aggravating the toxic problems the planet is already facing.”

In his report, Orellana acknowledges that “climate change poses an existential threat to humanity and the effective enjoyment of human rights.” Nevertheless, the report notes, in the race to “reduce greenhouse gas emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere,” countries and corporations are turning to technologies that can exacerbate pollution. Examples include waste from mining of the new “strategic” minerals, production of lithium-ion batteries without adequate means of recycling them, and a new emphasis on nuclear energy, which produces spent fuel rods that remain radioactive.

Mining, in particular, “is one of the most contaminating industries in the world,” he told InquireFirst, affecting human rights protected under international treaties, including the rights to life, health and a healthy environment. “These impacts often fall particularly heavily on vulnerable groups and peoples, such as Indigenous peoples, which aggravates both environmental injustices and environmental violence.”

The lure of the ‘lithium triangle’

A conventional automobile contains about 34 kilograms of metal, mostly copper and manganese. An electric vehicle contains more than six times that amount and a greater variety — graphite, copper, nickel, manganese, lithium, cobalt and a small amount of minerals known as rare earths. As demand for electric vehicles continues to climb, more — and larger and deeper — mines will be needed, many of them in countries where mining is already a source of conflict.

WHAT MINERALS ARE IN A LITHIUM BATTERY?

Grams and percentage of total

*Others include: Manganese: 10 grams (5.4%); Cobalt: 8 grams (4.3%); Lithium, 6 grams (3.2%) and Iron: 5 grams (2.7%)

In Latin America, the energy transition has shone a spotlight on lithium, the lightest mineral and one that is critical for the manufacturing of rechargeable batteries that power everything from cell phones to electric vehicles, and which are used to store energy produced by solar grids. Until recently, there was little demand for lithium. But production has risen dramatically in the past decade, and the mineral is at the center of geopolitical power plays that reach deep into South America.

In 1995, global lithium production was 9,500 tons, and the United States was a major producer of the mineral, which was mainly used to strengthen glass and ceramics. By 2010, however, global production had doubled, and Chile had become the world’s top producer. Over the next decade, lithium production quadrupled, reaching 106,000 tons in 2021.

Source: www.weforum.org

In its 2023 report on lithium, the US Geological Service stated that the the world has an estimated 98 million tons of lithium resources — the amount of lithium known to exist in the Earth’s crust — and an estimated 22 million tons in “reserves,” the amount that could be recovered economically using currently available technology.

Llithium resources

(millions of tons)

TOTAL - 97.28

* In mid-2023, Bolivia anounced an addition of 2 million tons for a total of 23 million

Source: United States Geological Service, 2022

Lithium can occur in the brine of salt flats, like those in Argentina, Chile or Bolivia, or in hard rock, like the deposits in Australia and Peru. China has both types of deposits. The different formations requires different mining techniques and imply different environmental costs.

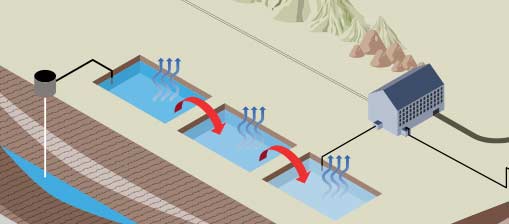

In salt flats, the brine is pumped from underground into huge ponds, where the wind and sun evaporate the water, leaving the lithium to be extracted and processed. This is the least expensive form of mining, but the most water intensive, using about 528,000 gallons [2 million liters] of water per metric ton of lithium. A process known as direct lithium extraction could reduce water use, but it is still unproven at a commercial scale.

Extracting lithium from hard rock deposits requires less water, but displaces communities, leaves gigantic gashes in the earth, flattens mountains that may be sacred to nearby Indigenous peoples, and results in pollution of land and water. Some experts suggest that geothermal sources could yield lithium with a smaller environmental and climate footprint, but such reserves so far are only a tiny percentage of the world’s deposits.

About half the world’s known lithium deposits are found in the salt flats of the “lithium triangle,” a high, arid region straddling the borders of Chile, Argentina and Bolivia. Chile leads the world in reserves, with 9.3 million tons, followed by Australia, with 6.2 million; Argentina, with 2.7 million; and China, with 2 million, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Bolivia is reported to have some 23 million tons of lithium resources, but is not yet producing commercially.

Global lithium reserves

(millions of tons)

TOTAL - 26

*Bolivia does not have internationally certified reserves

Source: United States Geological Service, 2022

"Lithium triangle"

UYUNI SALAR

OLAROZ SALAR

SALINAS GRANDES

ATACAMA SALAR

SALINAS DEL RINCÓN

SALINAS DE ARIZARO

POCITOS

Chile surpasses Australia in reserves, but has slipped to second place in production. Various countries have talked of developing the capacity to manufacture products for the renewable energy industry, thus adding value to the raw materials being mined. So far, however, only China has made strides in that area, although the United States is implementing incentives aimed at reducing dependence on Chinese mining and processing.

Global lithium mine production

(tons)

Source: United States Geological Service, 2022

Nevertheless, experts caution that predictions of future demand for energy-transition minerals could change drastically as technology changes. For example, one projection sees lithium demand increasing by a factor of 13 by 2040, while another predicts that demand will rise by a factor of 51. If other substances replace lithium, mining projects that are currently on the drawing board could become obsolete before they even begin production.

Is a ‘just transition’ possible?

But what can be done to ensure a “just transition” in places where lithium mining is already under way or is poised to begin?

Most of the regions of Latin America with the largest reserves are arid lands mainly inhabited by Indigenous and other traditional farming communities that are already dealing with water stress. In Argentina, Indigenous communities in the lithium-mining region of Juanjuy staged a protest in August against regulatory changes that they say would make it easier for the government to expropriate their land, much of which lacks legal title. In Chile, communities are divided about lithium mining in the country’s northern Atacama desert. The same is true in Peru, where the government has signaled its intention to support hard-rock lithium mining, but where communities have little information.

In recent decades, Latin American communities have increasingly pushed back against all kinds of mining, but companies and governments often divide and conquer, drumming up support with the offer of jobs, then pitting supporters against opponents in communities.

Legislation meant to protect communities’ interests, such as International Labor Organization Convention 169, requires that Indigenous and tribal peoples give their “free, prior and informed consent” before development projects, including mining, can go ahead on their lands. In practice, however, communities generally do not have veto power, and in some countries, including Peru, the consent process only occurs after the exploration phase, when governments are unlikely to halt a promising revenue-producing project.

The lithium boom adds urgency to questions of whether to mine, and if countries choose to go ahead, how to do it in a way that does not place local communities at an even greater disadvantage.

For Lisa Sachs, director of the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment at Columbia University in New York City, the contradiction implicit in the use of “dirty” mining to provide “clean” energy implies a global balancing act.

“It inevitably comes down to trade-offs, because there is no way right now to produce the materials that we need for our economy without having some impact on the planet and [without] mining,” says Sachs. “So even in the best-case scenario, which we are far from, resource extraction and resource use inherently require trade-offs.”

The question is to how to minimize the cost to vulnerable communities, she says. And that doesn’t mean being content with business as usual, because the field is changing rapidly. “It’s inherently dynamic,” Sachs says, “because the technologies that we have, and the knowledge that we have about how to do things better, are constantly evolving.”

“Doing things better” requires action by both the countries where the demand for lithium is greatest, including the United States, China and the European Union, and Latin American nations with lithium reserves, Sachs says. She sees the European Union’s plan for a circular economy — which emphasizes waste reduction — as a positive step.

“We should be building more circularity into the economy, [including] in end-use products [and] the mining process itself, because it generates so much waste that still has valuable resources in it,” she says.

Substitutes for some of those materials are also likely to be developed, she adds — scientists are already experimenting with alternatives to lithium-ion technology for batteries, with sodium showing the greatest promise so far.

“All of those things should be very much on the table and part of this agenda, which is how to decrease demand so we can mitigate or reduce the trade-off, even if some trade-off is inevitable,” Sachs says. But that trade-off should be accompanied by benefits for the countries that produce critical minerals, she adds.

Region faces ‘new challenges’

“The energy transition is a massive agenda, and it should be accompanied by a massive development agenda,” Sachs says. “How are we going to finance this? How are we going to ensure that the poorest communities are benefiting and are not being disproportionately harmed?”

That question is particularly complicated because many countries where “strategic” minerals are found are already economically dependent on mining, and many have a fraught history of resource extraction. For Anabel Marín, a research fellow at the Institute of Development Studies in Brighton, England, the quest for a just energy transition offers an opportunity to do things differently.

“We have new kinds of challenges, but hopefully also new opportunities,” Marín says. “ “I see governance as a process that [involves] not just the action of governments, but coordinated action between companies, governments and civil society,”

Greater participation in decision making is crucial, but giving marginalized groups a seat at the table is not sufficient, she says. Demands being made by communities affected by mining in recent decades should lead to changes in policy.

Participation is needed “not just in decision making, but also in knowledge and innovation,” not just in technology, but also in policies, she says. “The key to change is knowledge and innovation – we need to do things in a different way.”

Historically in South America, “people who come to power ask how other countries have done these things,” Marín adds, “but these are new challenges, and we need to experiment. We need policy innovations, and you can’t do policy innovation without experimentation.”

For Orellano, the UN special rapporteur, it is crucial that countries combine policies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions with policies for reducing pollution and restoring ecosystems. Those are issues he plans to present during the next UN Climate Change Conference, to be held in Dubai in early December.

“We hope that will influence national policies that governments adopt,” he says, especially in three areas.

One specific policy he would like to see countries adopt is a ban on mining in protected areas. Another is ratification and implementation of the . Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, also known as the Escazú Accord, which requires countries to ensure that communities affected by extractive industries have timely access to information, participate significantly in decisions affecting them, and have access to justice if their rights are violated — a key provision considering that Latin America is one of the most dangerous regions in the world for people who defend the environment and their territories.

A third policy area, he says, is regulation of contaminants and waste associated with the energy transition, he says, adding that countries must not relax environmental and social safeguards just because the minerals are needed to counteract climate change.

“Extractive industries have seriously affected the environment and the effective enjoyment of human rights around the world,” he says. “Minerals like lithium are important for addressing the climate crisis, but that doesn’t justify repeating the errors of the past and aggravating the poisoning caused by pollution from extractive industries.”

By salting or by hard rock mining.

Lithium in Bolivia: a treasure impossible to unearth?

In Bolivia, after 15 years of talking about lithium, there is little production and no industrialization.

In Peru, more questions than answers about lithium

Peru is still on the sidelines, though. Its lithium is in rock formations that also contain uranium. A company has held concessions in the area for nearly two decades, but so far mining is still in the study phase.

Lithium in Mexico: between the promise of development and the reality of environmental damage

The Mexican government's interest in exploiting lithium and the arrival of companies like Tesla could create sacrifice zones in the north central region of the country.