In Bolivia, after 15 years of talking about lithium, there is little production and no industrialization.

The beauty of the Salar de Uyuni is indescribable, with endless roads that get lost on the horizon. The 7,400-square-mile salt flat located in the department of Potosí, Bolivia captures the eye with its astonishing fusion of the azure and pure white of its surface. Considered one of the natural wonders of the planet, the Salar de Uyuni not only stands out for its beauty but also for hosting the world's largest reserve of lithium, a key natural resource for the transition to green energy. Beyond its spectacular natural beauty, the Salar has generated a whirlwind of dreams and possibilities for Bolivia.

Lithium is seen as a pillar of economic development in Bolivia and has awakened enormous expectations. But to achieve that, the mineral must be extracted, a battery industry must be developed and the industrial process that began 15 years ago must be strengthened. For people like Efraín Quispe, Jiliri Mallku of the Council of Original Autonomous Government of Marka Tahua Aranzaya Maranzaya, those expectations have become frustrations. "Totally disillusioned. We've reached that point," he says with resignation in his voice.

Debris left in the middle of Salar de Uyuni as a result of mineral exploitation.

Debris left in the middle of Salar de Uyuni as a result of mineral exploitation.

Bolivian President Luis Arce Catacora described the lithium industry as a "strategic horizon" for the economy and promised that "by the first quarter of 2025, Bolivia should be exporting lithium batteries with national raw material.” But the deadline is rapidly approaching and the mission seems condemned to failure.

A Dollar Dance

It has been 15 years since the federal government began to talk about lithium extraction for industrial use. But it has not yet laid the foundation for industrial production, despite having the largest lithium reserves in the world with 23 million tons in the Uyuni (21 million) and Coipasa (2 million) salt flats alone.

There are barely even fledgling efforts to produce lithium on an industrial scale. Factories designed to produce lithium batteries for automobiles and cell phones are still in the pilot phase.

But in the government, the dollar dance around this coveted mineral does not stop.

The inauguration of the Lithium Carbonate Industrial Plant in the Salar de Uyuni, Llipi region, was announced for August 6, 2023 (something that just happened on December 15, 2023).The plant has a production capacity of 15,000 tons per year which, if sold at $40,000 per ton, would bring in $600 million for the country, according to estimates by the Vice Minister of High Energy Technologies, Álvaro Arnez. But it is still on hold.

The figures go beyond that. As a result of four contracts signed by the federal government with three Chinese companies and one Russian company in January and June of 2023, the projections for 2025 are to produce more than 100,000 tons, including those of the Llipi plant, which belongs to the state-owned company Yacimientos del Litio Bolivianos (YLB), and to put $9.6 billion into government coffers as of 2026, said the Vice-Minister of Exploration and Exploitation of Hydrocarbons, Raúl Mayta, in published statements.

Although the millions of dollars that could enter the country through industrialization have not yet entered this dollar dance, it has created enormous expectations among the people who live near the Salar de Uyuni. They believed the plants could be located in different communities so that some could produce battery casings, for example, and others, battery components.

"It has been 15 years with an allocated capital of slightly more than one billion dollars and there is not even raw material (for industrialization)," says Pablo Villegas, an expert from the Documentation and Information Centre (CEDIB) in Bolivia, which monitors the exploitation of lithium. Although the country produces raw material, Villegas says “it is still a product in the pilot phase.”

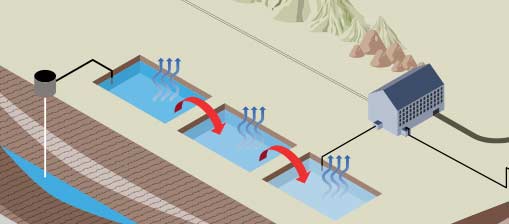

Currently, the pilot phase of lithium production is performed under the evaporation system, and YLB will apply this model in the Llipi Lithium Carbonate Plant. But with the signing of contracts between the federal government and the Chinese and Russian companies, the raw material will be obtained through Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE), according to Lino Barahona, YLB's Operations Manager.

Far from industrialization

In this whole process, the most critical aspect is industrialization, says Villegas, who affirms that the country has not advanced in technological innovation and in the registration of patents for the production of lithium batteries.

If the country fails to obtain its own patents, he warns, it will be forced "to buy the patents and end up paying for the intellectual property of others, which means it will end up working for the owner of the patent.”

Theoretically, Bolivia will have more than 100,000 tons of lithium per year as of 2025, which will allow it to reach industrialization and/or battery production phase, according to the government's proposal. However, the CEDIB expert notes that in order to produce a battery, not only lithium is required (which is 3.5% of the final product), but also other types of minerals and technological elements.

He explains that nickel and copper are needed, metals that may be available in Bolivia, but their extraction needs to be developed – a process that could take between five and ten years. Batteries are also made of cobalt and graphite, which are not available in the country and would have to be imported. The most troubling issue is that Bolivia does not produce energy semiconductors.

"Lithium exploitation … is already a failure. The time limits of the pilot phase expired years ago. Those years mean millions and millions in financial losses,” says the Jiliri Mallku of the Council of Original Autonomous Government of Marka Tahua Aranzaya Maranzaya.

That has destroyed the hope of creating sources of employment for local people, as they had been promised. "There is going to be a lithium company. We are going to hire your children. We are going to train them. They are going to be professionals,” Quispe recalls the government told them. "But that is a huge 'mamada' (deception).”

Shady contracts with foreign companies

In 2023, the government of President Arce signed four contracts for the installation of plants that will produce battery-grade lithium carbonate of 99.5% purity. The first contract was signed on January 20 with the Chinese company CATL BRUNP & CMOC (CBC), which will install two plants in the salt flats of Uyuni and Coipasa, each with a production capacity of 25,000 tons per year.

Then, on June 29, YLB signed contracts with Russia's Uranium Group One and China's Citic Guoan for the installation of two plants that will each produce 25,000 tons per year of 99.5% battery-grade lithium carbonate. In total, the three companies will invest $2.8 billion in the four plants.

But the contracts are being called into question because the government did not disclose the conditions under which they were signed. YLB simply issued a statement saying that "the implementation of the lithium carbonate industrial plants (is) under the sovereign business model.”

"Mr. Arce is a person whose government is standing out for increasingly distancing us from truth and transparency," said Daly Cristina Santa María, senator of Potosí for the opposition party Civic Community (Comunidad Ciudadana, CC).

For his part, Quispe recalls that, as native people in whose territory the lithium reserves are located, "we have requested hearings with government authorities and to date they have not granted us an audience" to discuss the issues related to the extraction of the mineral.

In turn, Villegas assures that the four contracts are only for the production of raw material and that at no point "has the government said that we are forcing the company to install the battery factory here.”

Fear of environmental impact

Even though the extraction of lithium and its manufacture for car batteries and cell phones have not entered the industrial phase, the people living near the salt flats of Uyuni and Coipasa are beginning to express their fears.

Efraín Quispe, the Jiliri Mallku of the Council of Original Autonomous Government of Marka Tahua Aranzaya Maranzaya, says that in these areas "there is no more rainfall and we are going to lack water practically everywhere. We are already suffering.”

Meanwhile, Víctor Copa, former Jilata Mallku of the municipality of Salinas de Garci Mendoza (Oruro), says that in order to irrigate crop fields and pastures, wells now have to be drilled for water. In the last ten years, rainfall has been scarcer than before, he points out.

Ingrid Garcés, a professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Mineral Processes at the University of Antofagasta (UA), has witnessed the impact of the lithium industry in Chile. In an article published by the web portal chilesustentable.net, Garcés said that "to produce one ton of lithium, 2 million liters of water are evaporated in the wells, that is, 2,000 tons of water that cannot be recirculated.”

In Salar de Uyuni, where will that amount of water come from?

The mayor of Colcha-K (Potosí), César Alí, believes that the water sources located in Puerto Chubica, Villa Candelaria, Río Grande and Colcha K, are the ones that will provide water for lithium extraction, although people have already expressed their refusal “to take care of that need.” However, YLB managed to persuade the residents of the Río Grande community, where the main water source is located and where wells have already been drilled to supply the Llipi Water Plant in exchange jobs for the residents of the town.

The CEDIB expert, Pablo Villegas, says the answer to how much water will be needed to exploit lithium must come from the environmental impact study. But in Bolivia, the government does not make those studies public. "The environmental damage can be very great, very great indeed. It can destroy the land and even contaminate the population," he warns.

Thus, the Salar de Uyuni, a natural wonder of Bolivia, and its inhabitants live at a crossroads, with the promise of lithium weighted against the potential of other industries such as tourism.

Tourism to Bolivia increased 35% in 2023, with a projection that 700,000 tourists would visit by the end of that year, according to Bolivia's National Statistics Institute. Although Bolivia is not one of South America’s most popular tourist destinations, the jump in visitors – up from 180,000 in 2022 -- shows there are possibilities for growing the industry.

Efraín Quispe, the local leader, says his community prefers to focus on "industrializing" the tourism industry rather than relying solely on lithium extraction. But he isn’t optimistic their demands will be heeded. The exploitation of lithium in Bolivia is inevitable, he says.

The toxic paradox of ‘green’ energy

By salting or by hard rock mining.

In Peru, more questions than answers about lithium

Peru is still on the sidelines, though. Its lithium is in rock formations that also contain uranium. A company has held concessions in the area for nearly two decades, but so far mining is still in the study phase.

Lithium in Mexico: between the promise of development and the reality of environmental damage

The Mexican government's interest in exploiting lithium and the arrival of companies like Tesla could create sacrifice zones in the north central region of the country.