CORANI, Peru. A dusty road wide enough for just one vehicle winds past a scattering of adobe houses and hillside pastures of spiky grass, finally dipping down to Corani, where the glass-fronted district government office overlooks a small plaza where the town’s name is spelled out in giant letters.

The chilly, windswept landscape has remained virtually the same for the generations of mainly Quechua farm families who have raised llamas and alpacas in this place, nearly 4,000 meters above sea level. But talk of change is in the air. Pastures in this part of Peru’s southern Puno region sit atop deposits of lithium, a mineral that has become vital for the transition from fossil fuels to other energy sources.

Lightweight lithium is a key component in batteries powering a range of everyday objects, from cell phones to electric vehicles. Across the high plain known as the Altiplano, Chile and Argentina are already among the world’s top producers of the mineral. Neighboring Bolivia is poised to join that club, as the three countries straddle the “lithium triangle,” which is covered with salt flats containing the mineral.

Peru is still on the sidelines, though. Its lithium is in rock formations that also contain uranium. A company has held concessions in the area for nearly two decades, but so far mining is still in the study phase.

That hasn’t stopped the company’s public relations machine and local rumors, however. And in a country where two out of three environment-related conflicts nationwide involve communities affected by mining, according to the government Ombudsman’s Office, some local residents favor a mining project, saying it will bring jobs, while others oppose it, fearing pollution. Almost all, however, end up saying that they haven’t heard much about what a lithium mine would entail.

Asked what expectations he has for the project, Corani Mayor Patricio Dávila turns his hands palm up.

“What expectations can I have if I don’t have any information?” he asks.

Elusive promise of riches

Despite its Andean mineral riches, including gold, much of which is mined informally or illegally, Puno is among the economically poorest regions in Peru. Four out of 10 people live in poverty, two-thirds of children between 6 and 35 months of age suffer from anemia — well above the already-high national average of 42% — and one in 10 suffers from chronic malnutrition. Corani, where nine out of 10 people live in rural communities, is the poorest district in the region. Another district in the same province of Carabaya is second poorest.

Nevertheless, mining of rare minerals — first uranium and now lithium — has been dangled for decades as the path to prosperity for the area.

Juan Tejada, coordinator of social programs for the Carabaya province, recalls similar excitement over announcements that uranium had been discovered near Macusani, the provincial capital. Hopes were dashed as uranium prices fell, only to rise again in 2018 when Macusani Yellowcake, now a subsidiary of the Canadian junior mining company American Lithium, announced that its Falchani concession, some 25 kilometers from Macusani, also contained lithium.

In media interviews, Ulises Solís, Macusani Yellowcake general manager, has said that the company has indicated and inferred reserves of a relatively modest 4.7 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent, the unit of measurement used by the industry. Further exploration is needed, however, to categorize those reserves as “proven.” The company’s environmental impact studies are currently under way, and he has predicted that construction could begin in 2026 and production in 2027.

In its financial statement for the years ending in February 2022 and February 2023, American Lithium said it had “not yet determined whether the properties contain ore reserves that are economically recoverable.”

Meanwhile, local residents have mixed feelings. One youth leader, who asked not to be identified, says many of his peers are hoping a mine would create formal job opportunities that would be preferable to hazardous labor in the informal gold mines in the northern part of the province, where the Andes slope down toward the Amazon basin. He and others worry about environmental impacts, however.

Betty Nélida Quispe Fernández, a leader of women’s organizations in Carabaya, fears that dust and water pollution from an open pit mine could contaminate pastures and fields of traditional crops like potatoes and kañiwa, a traditional high-mountain crop related to quinoa. The same fear extends to another concession in the area, where the Canadian junior Bear Creek Mining Corp. is prospecting.

If the lithium project does progress, local residents hope their province will get a fair share. Walter Churata Morocco, a teacher who is also president of the rural self-defense patrols, known as rondas campesinas, in Macusani, hopes it would create some 5,000 jobs for residents of Carabaya. “It has to have an impact on economic growth for Carabaya,” he says.

Nevertheless, he fears a mine could dry up rivers and springs, and he and Quispe worry about rumors that the processed lithium carbonate would be transported to Peru’s Pacific coastal ports through the neighboring region of Cusco, bypassing most of Puno.

Photo: Yda Ponce

Photo: Yda Ponce

In March, after a two-month protest against the government of President Dina Boluarte, which was particularly strong in Puno, traditional community leaders in the region announced that they would only allow lithium mining to go ahead if a battery-manufacturing facility was also built in the region.

Tejada sees little chance of that — “If we wanted to manufacture batteries, a lot of things would have to happen” first, he says. He says Macusani Yellowcake representatives floated the idea in presentations last year, but Solís discarded it in a recent media interview, noting that battery production requires other minerals, such as nickel and graphite, that Peru does not produce.

Meanwhile, discontent with the national government persists. Boluarte’s approval rating is among the lowest of Latin American presidents, at 12%. The memory of the protests of nearly a year ago, in which more than 60 civilians, six soldiers and a police officer died, is still fresh in the minds of people in Puno, where 18 of the civilians were shot. The resulting distrust in the government could make a mining project a harder sell, Dávila says.

Water among chief worries

The Corani mayor describes his district as having been “neglected by the state”, without police or courts, without adequate health care and education, where people live on what they earn from day to day. Publicity about lithium has raised people’s hopes that “foreign investment could lift Corani out of underdevelopment,” he says, but he and others are also worried about the impacts of mining.

Although he hasn’t seen specific plans, he says the lithium deposit is under the land of three rural communities in his district, and he doesn’t know what might happen to the people living there. Would they have to leave? How would they be compensated? And where would they go, when their lives have revolved around raising alpacas? “Taking away livestock raising here would be like taking away part of my body,” Dávila says.

He also worries about water. A preliminary economic assessment of the Falchani lithium project — prepared in 2020 for Plateau Energy Metals, which was acquired by American Lithium in 2021 — says water for the project would be drawn from local rivers. Local communities also rely on surface water, and Dávila says some springs are drying up, while some communities have seen their water supplies decrease as their population has grown.

Workers in mining camps will create even more demand for scarce resources, adds Dávila, who is also concerned about possible pollution of the rivers, which feed the Inambari River, which flows eastward into the Amazon basin. He particularly worries about Quelccaya, a community where Macusani Yellowcake is prospecting now, which depends on water from a glacier that has been receding since the 1970s. Even the glacier is now overlain with mining concessions, although it is also in a protected area, which could stave off exploration. Nevertheless, critics point out that the concessions violate a Peruvian law meant to protect the headwaters of rivers.

The national government recently launched talks with regional and local government officials to address Carabaya’s economic woes, but information about the proposed lithium mine is still lacking. Under Peruvian law, communities do not have rights to minerals under their land, so companies must negotiate with them for access. Peru has ratified International Labor Organization Convention 169 on the rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples, but since the agrarian reform of the 1980s, the Peruvian government has designated Andean communities as “campesino communities” instead of recognizing them as Quechua or Aymara.

As a result, companies are free to negotiate a “social license” to operate in those places, with no clear rules for the process, rather than going through a government-led consultation of the communities. Environmental impact studies are also conducted project by project, without examining the combined impact of multiple projects, especially in watersheds.

Marcos Orellana, UN special rapporteur on toxics and human rights, warns that access to information for communities affected by mining is especially important where exploration is under way for energy-related minerals such as uranium and lithium, and in places like Puno, which has more than 700 unremediated industrial waste sites, mainly from mining.

Marcos Orellana, UN special rapporteur on toxics and human rights, warns that access to information for communities affected by mining is especially important where exploration is under way for energy-related minerals such as uranium and lithium, and in places like Puno, which has more than 700 unremediated industrial waste sites, mainly from mining.

Orellana warns that “development” must not take priority over environmental protection and that in the race to replace fossil fuels, countries must not allow further contamination from mining of so-called “strategic” or “critical” minerals needed for renewable energy. Decarbonization, he says, not only must avoid future contamination, but must go hand in hand with “detoxification,” or the cleanup of sites that are already polluted.

“In the [Latin American] region and in the world, we see the proliferation of sacrifice zones — zones that are highlight contaminated, where people often live in poverty, lack voice and are condemned in the denial of their fundamental human rights,” he told Historias Sin Fronteras”.

Orellana insists on communities’ right to information and a voice in decisions about projects affecting them, as well as access to justice, including environmental justice.

“People who suffer from the contamination in these zones typically are marginalized from decision-making processes,” he says. “In Latin America, much remains to be done to make [communities’] right to access to environmental information a reality”.

The toxic paradox of ‘green’ energy

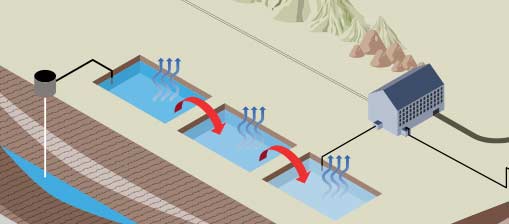

By salting or by hard rock mining.

Lithium in Bolivia: a treasure impossible to unearth?

In Bolivia, after 15 years of talking about lithium, there is little production and no industrialization.

Lithium in Mexico: between the promise of development and the reality of environmental damage

The Mexican government's interest in exploiting lithium and the arrival of companies like Tesla could create sacrifice zones in the north central region of the country.