A breakfast without arepas? An incomplete pabellón? Going to the beach and not finding the usual fish? Global projections of rising temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns are not favorable for the tropics where Venezuela is located. Local studies estimate that in the next few years the production of rice and corn, among other crops, will decline. At the same time, an invasive coral reef will push marine species away from the coast and fishing will decline. In a scenario where the government does not take timely measures, the consequences could change our food, social and economic dynamics in the not-too-distant future.

Emily was born into a family of cooks. All of the children in the family, from her oldest brother to Emily, the ninth, learned the art of cooking from their mother. Now 42 years old, Emily reminisces about her mother's cooking and immediately thinks of two dishes: pabellón — a platter of peasant origin consumed throughout the country, which contains rice, meat, caraotas (black beans) and fried plantain slices — and hallaca — a Christmas dish whose main ingredient is corn dough, stuffed with various meats and wrapped in banana leaves in which it is boiled— similar to the tamale in other countries in the region.

However, two of the main ingredients of both dishes, which are also essential for other basic dishes in Venezuelan gastronomy, are threatened by climate change.

According to the Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences (Acfiman), climate change in Venezuela will impact water supply and cause losses of up to 25% in crops, forcing more people into extreme poverty. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) issued a similar warning in its Study of the Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Food Security in Venezuela more than a decade ago.

Will climate change alter what we traditionally eat? How does a country and its people react to the loss of its most beloved foods?

"Identity is not something to be decreed, identity is to be lived, to be kept, it is part of memory," says Ocarina Castillo D'Imperio, an anthropologist and expert in anthropology of food. She explains that knowing and preserving our culinary heritage is the best way to take care of our food security in the face of climate change and an opportunity to rescue what we call identity.

"During the most severe moments of the crisis, between 2014 and 2016 (which, although not linked to climate change, showed us possible scenarios in the face of shortages), people had to go back to their family cookbooks. As imports contracted, people had to look to what was available, and what was it? Products from our native food pantry," the expert recalls. "For example, there were no grapes, apples or kiwis, but there were papayas, soursops and melons. Many people have discovered our carbohydrates, our tubers, which are still inexpensive and easily accessible foods, since they are part of our traditional popular agriculture and are not subject to agrifood chains, nor are they subject to the domination of imported seeds.”

The arepa is one of the most representative foods of Venezuelan gastronomy.

The arepa is one of the most representative foods of Venezuelan gastronomy.

Will we find in our native food pantries, and in sustainable and regenerative crops, an alternative to these agroclimatic predictions and an opportunity for the rescue of what we call identity?

While we search for answers, the increase in temperatures and the change in rainfall patterns threaten, among other crops, the most consumed in the country -- rice and corn. At the same time, an invasive species, a product of human misconduct, becomes both an unprecedented environmental disaster and the nemesis of fishermen along almost the entire Venezuelan coast, considerably reducing fishing. These natural and human-made disasters amid insufficient government measures put our food security at risk.

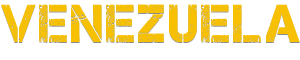

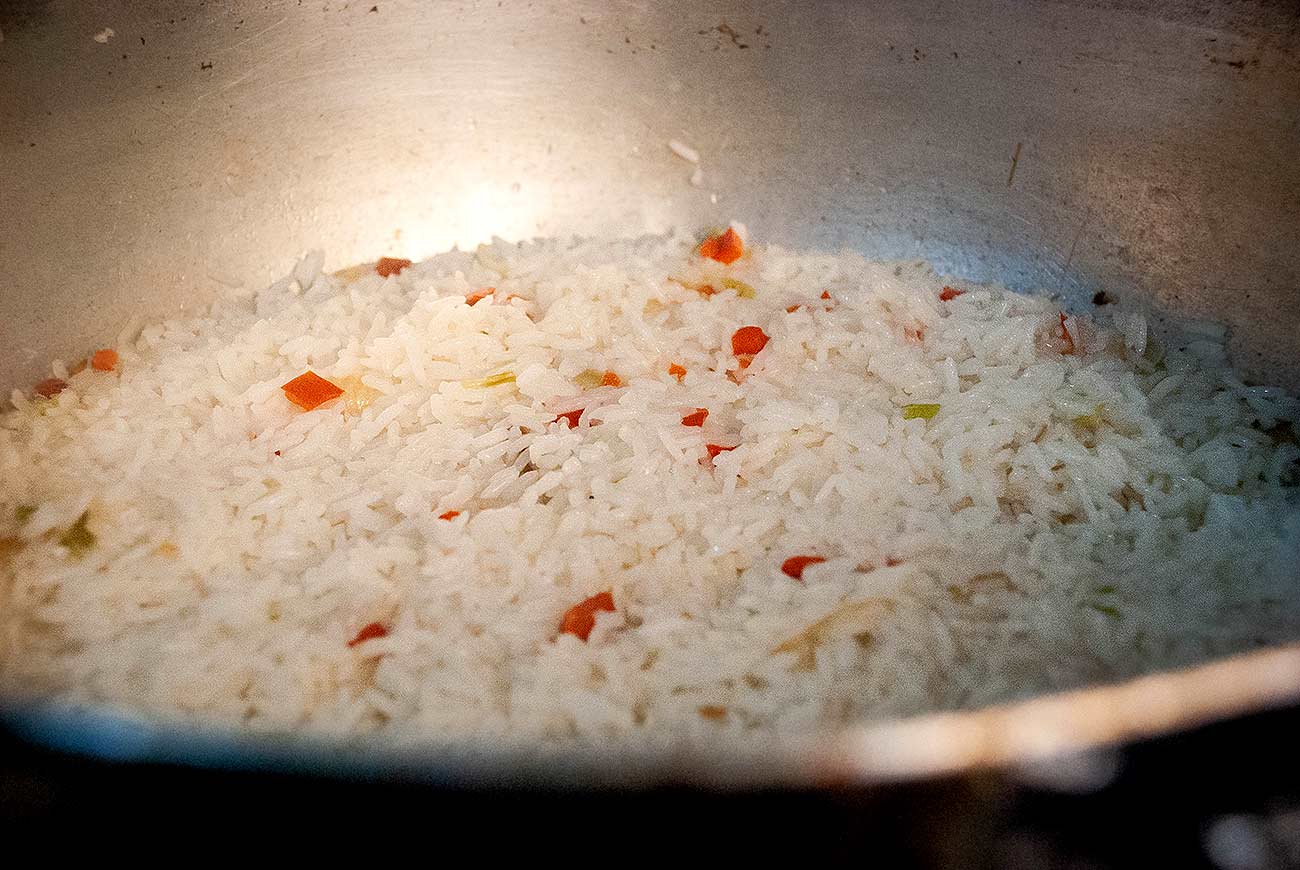

"A pabellón without rice is not a pabellón."

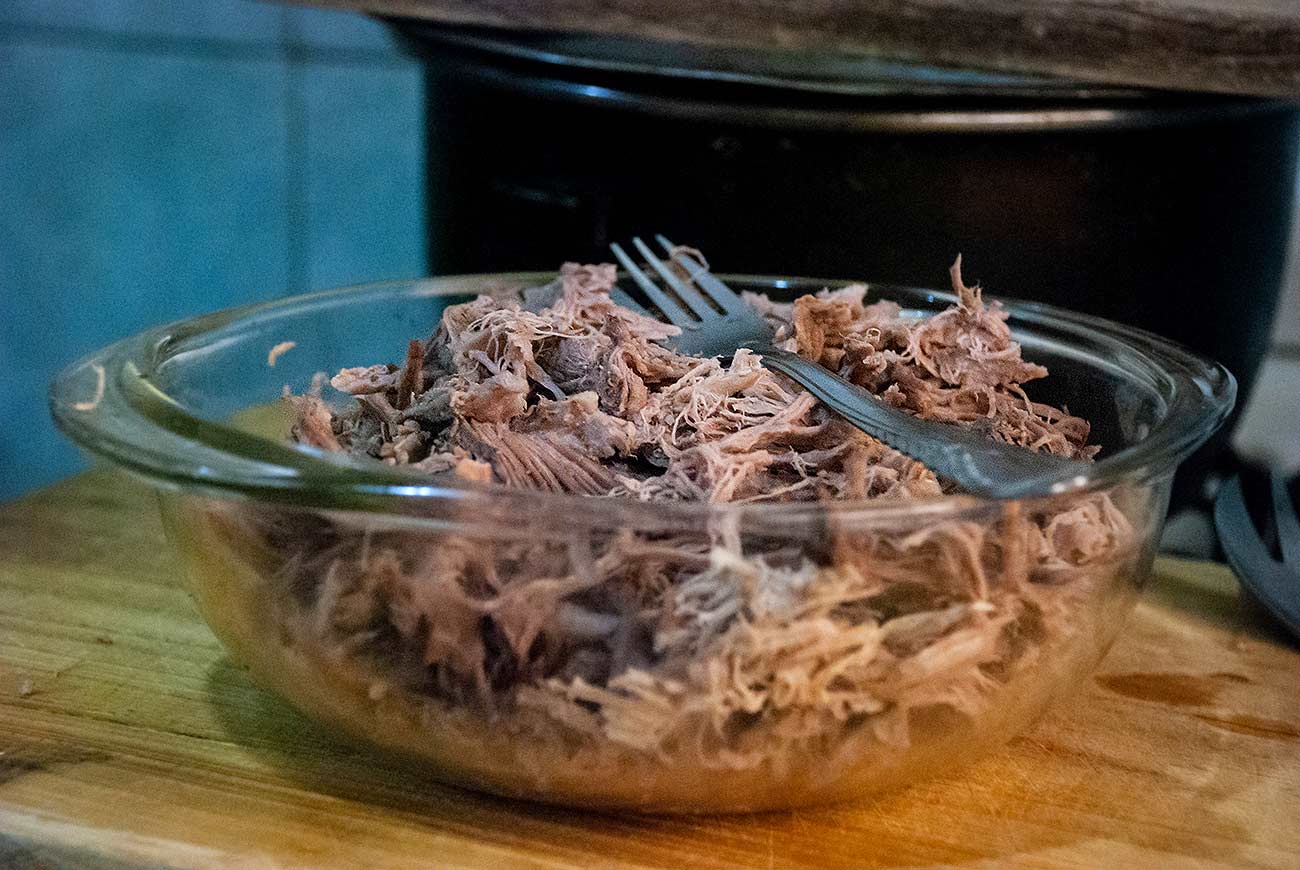

For the rice to taste good, Emily first makes a sauté. She puts garlic, paprika and onion in the pan and when they turn golden and the whole kitchen is filled with their smells, she adds the rice, which she previously rinsed. She sautés it a little, she says that this way the grain is cooked just right, no more and no less. Then she adds water and covers the pot. This is the penultimate step, before frying the plantain slices, which she prepares when she makes the pabellón: she prepares the beans and the shredded meat several hours in advance to make sure that everything is soft and well-seasoned.

Although it seems like the simplest ingredient in the dish, it is the rice that provides the neutrality with which all the other sweet and savory flavors contrast. "Without rice there is no pabellón," Emily says, and it's true.

But according to agroclimatic projections, the rice of Emily's pabellón —an essential ingredient on every Venezuelan's plate— is at risk.

"The main climatic factors affecting agriculture are changes in temperature and precipitation. Extreme patterns in both factors are increasingly constant and their effects are detrimental; such is the case of droughts, floods, and extreme heat waves, for which it is difficult to have adaptation measures," explains Aníbal Rosales, agricultural engineer of the Orinoco Group organization and part of a group of 60 specialists from different areas working on Acfiman's Second Academic Report on Climate Change in Venezuela (DRACC).

Rosales warns that, according to projections of a study by the Agriculture Group of the Second Climate Change Report, by 2060 in Venezuela there will be reductions of up to almost 200 mm of annual precipitation in the eastern part of the country and very little reduction in the western regions. In terms of temperature, variations of 1.8° C are estimated.

The projections that seem far off, but the changes in temperature began to affect Venezuela’s rice crops in 2018. That year and the following year, nighttime temperatures in Portuguesa, Guárico, Cojedes and Barinas, states in the country's plains region, rose to 25°C.

This increase in temperature, at a time when plants are breathing, resulted in crop failure. As the environment warms up, the plant needs to breathe more. It becomes stressed and consumes more carbohydrates, failing to fill the rice spikelets. The result is immature plants that are unable to form the grain.

Rafael Javier Rodríguez, an expert in agroclimatology, member of the National Academy of Engineering and Habitat and co-author of the research carried out by Acfiman, explains that Venezuelan crops were facing the aftermath of the El Niño phenomenon. He says that after the loss of crop yield, "etymological, phytopathological and physiological studies were carried out on the immature grains, and it was determined that the fundamental cause of the damage was of a climatological nature.”

Although the situation improved in subsequent years, rice has not been completely spared from the climate change onslaught.

For the preparation of the Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, "irrigation needs and crop yields were evaluated in the condition of rainfed agriculture, representative of the country (i.e., crops in which only rainwater is used, without the intervention of artificial irrigation), for the region comprising the states of Portuguesa, Barinas and Apure.” According to the study, in the worst-case scenario, rice crops in Venezuela could lose a third of their yield in the coming decades.

Rice yields in Venezuela already ranked second to last among the main agricultural countries in Latin America in 2021, according to FAO statistics, surpassing only Bolivia. By 2021, it had fallen below the Latin American average by approximately 4,400 pounds per 2.5 acres. "The deficit of rice productivity in Venezuela is clear, with the paradox of having lands with very good aptitude for this crop,” says Aníbal Rosales.

Rice yield (2021)

Rice production (2021)

According to the Confederation of Agricultural Producers' Associations of Venezuela (Fedeagro), in 2022, rice had a planted area of about 210,000 acres, with an estimated production of 429,740 tons, which represented an increase of 79% over the previous year.

"Growth was basically concentrated in the areas of influence where irrigation is by gravity, it requires less fuel and the water rate is lower. Farmers had new genetic materials with good yields that encouraged them to increase the planting area. The climatic year favored the crop and the new varieties responded productively, reaching an average yield of around 11,000 pounds per 2.5 acres," details the report, issued in March 2023.

Although recent facts are encouraging, Rafael Rodríguez warns that if El Niño consolidates in 2023-2024, the 2018 scenario could return during the first months of next year, due to an increase in the minimum temperature. Rice production could decline to the point of not meeting national demand and rice on Emily's dish —on our dishes— could again become scarce.

The invasive coral reef that leaves us without fish

Oil seems to crackle when it comes into contact with fish and, almost immediately, the smell of the Caribbean takes over the entire kitchen. The fish is fried and browned in a familiar scene that began many hours before, when the fishermen went to the open sea. The fish is gutted, scaled, and then distributed, first on the coast, then in markets throughout the country. In Venezuela, fried fish is an essential dish. At the beach, in homes, restaurants...always accompanied by tostones (fried green plantain) and salad.

But invasive species know no traditions.

Unomia stolonifera, a fast-growing soft coral native to the Indo-Pacific that is commonly known as the “stoloniferous fire coral,” first appeared between 2000 and 2005 in Mochima National Park, a coastal town in the eastern part of the country. The theory of community of biologists who study its expansion is that a person dedicated to the illegal trade of marine species planted it off the coast of Venezuela to reproduce it for sale. Every now and then, the trafficker returned to collect the abundant harvest.

But suddenly, the coral began to grow in an unexpected way, affecting the seabed. As biodiversity began to disappear, so did the marine life trafficker, who so far has not been identified.

With no predators and favorable climatic conditions, Unomia began to grow at a dramatic rate of almost 11 square feet every two months, in contrast to brain corals, for example, which grow about 0.39 inches every two years. It began to cover everything in its path with a slimy and smelly texture, until it could no longer go unnoticed.

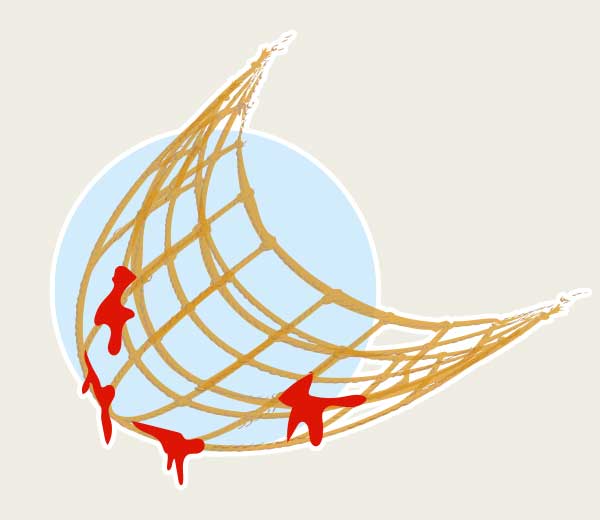

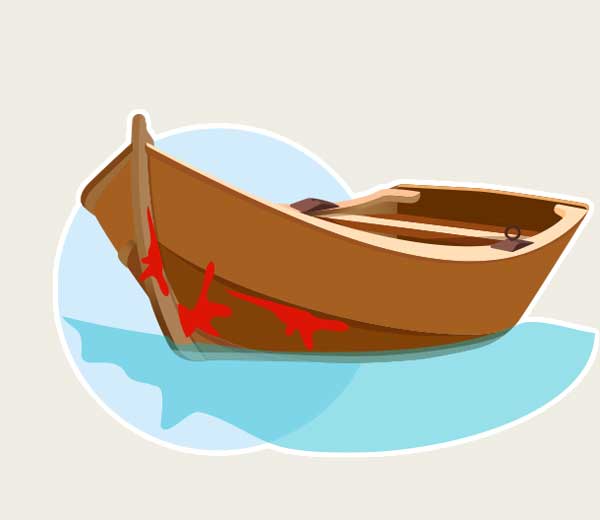

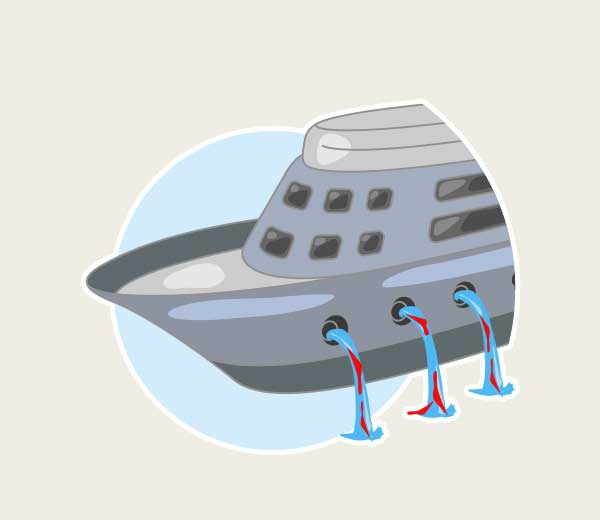

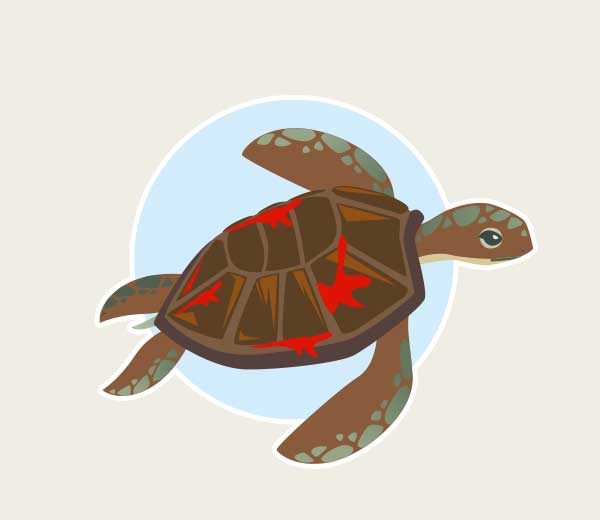

Dispersion types:

Fragments that get caught in fishing nets and return to the sea in different places

Ship's hulls and anchors

Ballast water

Turtle, crustaceans, and crabs’ shells, plastic and glass bottles, to which fragments adhere and are then transported to other sites

Natural dispersal through coral larvae

Source: Unomia Project and Fundación Arrecifes de Venezuela

But why does its presence represent a threat to food security, at least in principle, in Venezuela? Because the Unomia not only grows faster than our local corals, it also kills them. And the reef species that shelter, reproduce and breed in these spaces are moving to others in order to survive. The result? A steep decline in fisheries.

"The species most affected by this coral are the benthic species associated with reefs. Among the commercial species, that is, those that directly affect humans, are the white grunt, bigeye, grouper, snapper, pompano, shrimp and octopus," says Mariano Oñoro, coordinator of the Unomia Project, founded to gather experts to search for a solution to "an environmental disaster of unprecedented dimensions.”

Oñoro explains that, given the increasingly frequent absence of reef species, the fishermen of the Mochima coast who make their living from artisanal fishing now depend on species that arrive in shoals on a seasonal basis.

According to Gloris Muñoz, president of the Mochima Chamber of Commerce and Tourism, the state of Sucre (where the national park is located) is the source of 70% of the country's fish. However, according to Sonia Rivero, spokesperson for the Sucre State Fishermen's Front, some species have completely disappeared. "We used to fish John Dory, slope bass, sea robins, bigeye, and stone bass at night, but now that no longer happens because they have gone to the depths,” she said in an interview with the local news organization Crónica.Uno. She noted that the fishery dropped to 45%. They used to pull 16 tons of fish out of the sea each month. Now they don’t even get 1,100 pounds.

Clima 21, the Venezuelan Observatory of Environmental Human Rights, reports that fishing in Venezuela has fallen 80%, causing the "loss of more than 20,000 direct jobs and an average reduction of 40% in family income in fishing communities. Those startling numbers have created an urgent concern that Unomia is contributing to food insecurity not only on the coast but throughout Venezuela.

The decline in fishing is not the only consequence of Unomia affecting the economic and social dynamics of coastal towns. Its presence, in many cases, from the shore, at a depth of just 2 inches, is affecting the second major income of these communities: diving.

At the bottom of the sea there are different types of ecosystems: there are sandy seafloors, rocky seafloors, coral reefs, seagrass meadows, mangrove forests and, to a greater or lesser extent, Unomia is affecting them all," says Oñoro. María Olga Sánchez, a professional diver who directs the Fundación Arrecifes de Venezuela and who collaborates with the Unomia Project with underwater cleanup and coral reef detection in the center of the country, reports that this "has transformed paradisiacal beaches into beaches with a slimy seabed, which smells very bad, is very unpleasant to the eye and to the touch and stains the skin.

She and her team have witnessed the arrival and reproduction of the invasive coral, as well as the death of all the marine life it covers due to lack of oxygen, at a faster pace than the scientists’ solutions. "The largest colony we have in the state of Aragua is in Valle Seco, Choroní. Where there used to be a natural breakwater full of beautiful coral reefs, today the Unomia occupies approximately 80% of the surface.”

Although warnings from marine biologists and other experts began in 2011, the government response didn’t come until 2017. Currently, there is a working group committed to finding a solution that is comprised of public agencies such as the Ministry of People's Power for Ecosocialism, the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Socialist Institute of Fishing and Aquaculture, as well as private organizations, such as researchers from the Central University of Venezuela, the Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research, the University of Oriente, the Centroccidental University, the Oceanographic Institute of Venezuela and the Unomia Project.

They are waiting for authorization to test a mechanical extraction method: an experimental prototype that works with ultrasound and turbines, to pulverize the coral and send it to the seabed as organic matter. Only then will they know how efficient it is and whether it causes collateral damage. And only then will they also know if our biodiversity and the marine species that are part of our gastronomy have any hope of survival.

The uncertain future of arepas

With butter and cheese, with avocado and chicken, with seafood, with beans and plantain slices, with scrambled eggs, with stewed fish, with meat, with pork, always freshly made with white corn flour in a hot metal griddle. For Venezuelans, the arepa is an all-important food. It is eaten every day for dinner, and even at lunch with sancocho (a traditional stew). Its replacements -- the empanada or bollitos hervidos (dumplings, sometimes seasoned) -- are made with the same ingredient: corn. Even the most representative dish of Venezuelan Christmas, the hallaca, would be impossible to prepare without this versatile grain.

Its production in recent years has had ups and downs and, although the current outlook is positive compared to recent times, its production in the country is only enough to cover between 15% and 20% of domestic demand. In the past, production was as high as 80% of demand.

In 2021, NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and The Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York City, determined that as a result of climate change, corn crops could fall by 24% by 2030. Climate change would make it more difficult to grow corn in the tropics and, therefore, in Venezuela.

"A 24% reduction is not the same in an underdeveloped country, truly underdeveloped, such as Venezuela. It must be considered that by 2030, in the country, corn will continue to be a (main) food for the people. Aricultural production will surely continue to be scarce, the demand will not be covered and, therefore, imports will continue in order to satisfy the deficit,” says Aníbal Rosales.

Agroclimatologist Rafael Rodríguez points out that more focused studies project that this drop in Latin America and the Caribbean will reach at least 10% by mid-century, extending to other crops such as rice and beans. But he also says it is important to consider that agriculture responds not only to biological issues, but also to non-biological ones, such as infrastructure and the use of fuels or agrochemicals, which is a determining factor in yield and production.

For his part, Rosales adds that "the agricultural sector of most Latin American countries has occupied an important place in the economy of those countries, contributing an important portion of their Gross Domestic Product (...), while the Venezuelan agricultural sector faces deficits in supplies, credits, agricultural machinery, irrigation.” He says it does not matter how many contributions are made from science if there are no government policies to support them.

Berno Stanic, executive of FEDEAGRO in the corn sector, agrees with both experts in this regard: "The drop that occurred since 2014 was due to external political or economic conditions, due to the decline in planting areas and in the purchasing power of financing programs, which did not optimally assist crops, due to the lack of supplies, until in 2018 we hit rock bottom.”

However, he disagrees about the future of crops. "It is true that in the Corn Belt in the center of the U.S. there has been a drop in production in recent years, due to climate change. But globally, in some areas this has affected yields and in others it has benefited them. Climate change affects the northern cone and the southern cone differently. It does not affect us all in the same way. In Brazil, for example, yields have improved.”

He admits that this is due not only to climate but also to government factors, "such as climate change adaptation policies, which have made it possible to open new planting fields in this country, where the government has supported the agriculture sector.” But he is also optimistic about the future of corn in Venezuela. "Since 2019 we have had a slow, but steady recovery. From the crisis, we learned to be a little more efficient in the field."

Corn yield (2021)

Corn yield (2021)

Stanic does not deny the effects of climate change and admits that "in Portuguesa state, in Santa Rosalía, the heart of Venezuela's granary, we have regions where planting areas are quite advanced, while in others, in the same state, the rain has not allowed planting.” But he urges experts to be cautious. "At the beginning of the year, climate experts recommended, even directly to farmers, not to advance plantings in May, as is usually done, because El Niño would come and damage them. But, on the contrary, it has rained a lot.”

In this scenario of a government that remains silent in the face of an apparently irremediable and uncertain future, what is the solution to keep arepas on our plates? Rodriguez asserts that the way forward is that "material or genetic research should lead to the use of drought-tolerant materials, an architecture that tolerates strong winds and adapts crops to our projections of rising temperatures.”

In short, in the face of climate change that threatens our crops, all experts agree on one thing: we must look for foods that are part of our native food pantry, whose agroecological patterns are sustainable, with new methods that are soil regenerative and recognize that our culinary heritage is greater than we think.

It is also an opportunity to rescue what we call identity. "At this stage of the game we know that what generates our food memory are these images that remain engraved in our brains and are associated with our past and our family life, our family history," says Castillo D'Imperio.

Arepas are part of my identity because I've been eating them since I was a child. My grandmother used to make them, so did my nanny. We used to buy them in an arepa factory that made them in Catia (when they were still made of corn and not flour), near my house, where I used to go on foot with my mother, when I was 5 or 6 years old on Saturday mornings. I used to bring the warm arepas in a little brown paper bag, and I didn't know what was better, to smell their exquisite fragrance coming out of the little bag in my arms, or to eat the. That is identity.”