The seaweed rush has sparked a black market in the underwater forests of giant kelp that grow in Chile’s coastal waters. The overexploitation of kelp forests, the “nurseries” of the sea, is damaging the ocean ecosystem. Scientists and fishermen are looking for ways to sustainably extract the giant kelp and respond to future environmental threats such as climate change. Lab-grown super algae could be part of the solution.

"The island doesn't leave you alone," says Marcos Callejas, sitting on a seaweed bale on Santa Maria Island with a portable speaker on his lap playing loud trap music. Although the price of seaweed has dropped by two-thirds in the past couple of months, from $1.50 to just 50 cents a kilo, Marcos is not complaining. He’s relieved that there aren't as many poachers on the island as when the price was at its peak. "Last December this was full of motorboats. From the shore, we could see how they would go out to sea to cut the giant kelp, but we couldn't do anything about it," he says.

"This island is blessed," he says. Marcos tends to throw out those kinds of short, deep sentences that don't seem to fit the music he is listening to. Today is a day that underscores what he says -- there is a strong wind and ocean swells. What for other fishermen is bad weather, for the seaweed gatherers is a blessing. With the swells, the largest algae are released from the underwater forests and float ashore. Today there is so much giant kelp on the beach that there is a lack of hands. In fact, the group formed by Marcos and six other people will not be able to collect it all and in the afternoon the sea will take the seaweed back. The sea gives, the sea takes.

The work of the seaweed gatherers on Santa Maria Island, off the coast of the Atacama Desert, starts at 7 in the morning. They kayak across to the island and then walk for about half an hour to the seaweed beds, small bays where the precious giant kelp — the reason they decided to settle in this desolate place where there is nothing but stone, salty wind and lizards — washes ashore.

Most of them arrived more than 10 years ago and got hooked. They settled on the coast with a view of Santa Maria Island in a village of about 40 wooden houses. Dogs abound, no one wears sunscreen and almost everyone, even the children, are expert swimmers and rowers. Most of the dogs were not brought by the residents. They are abandoned by their owners from a nearby city, Antofagasta. " We end up adopting them, we can't let them die," says Leandra Maluenda, seaweed gatherer and Marcos' partner.

The village where Leandra and Marcos live is called Caleta Errázuriz, and there most of the seaweed gatherers are women. The presidency of the group has, in most cases, been held by a woman and has led to the village being known as "the cove of the matriarchs.”

The first to arrive was Carmen Castillo, who settled down in a tent. Currently, Carmen's daughter, Samira, is the president of the group of seaweed gatherers.

Samira has tanned skin and moves nimbly along the beach despite her advanced pregnancy. Although she is not currently working in seaweed harvesting, she is meeting with authorities. Sometimes, the authorities and some academics treat them as predators because they harvest the giant kelp, she says. Samira wants the government to provide them with a management area so they can work without criticism or reprisals.

Samira insists the seaweed gathers are the most interested in conserving the resource. "When they cut it, it takes a long time for the giant kelp to grow and we are left without algae for a long time... how can we want it to end if this is what we live on?”

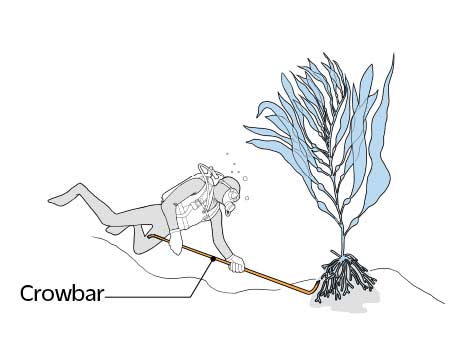

In areas that are not run by a fishermen's organization, only seaweed that floats ashore can be legally harvested. But when market prices are high, it is common for poachers to enter the underwater forest to "barretear.”

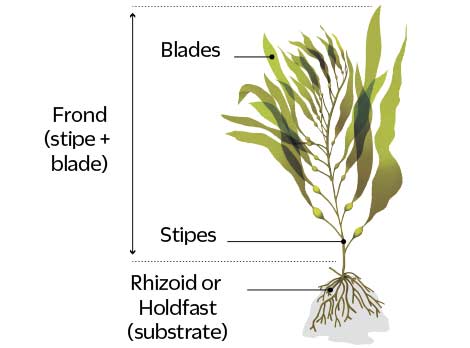

In areas that are not run by a fishermen's organization, only seaweed that floats ashore can be legally harvested. But when market prices are high, it is common for poachers to enter the underwater forest to "barretear.” This technique consists of cutting the giant kelp from its holdfast, a root-like structure that anchors the algae to the sea floor. That is what the inhabitants of Caleta Errázuriz saw during December 2022, when the price of giant kelp reached a historical high — almost $2 per kilo — due to the high demand, mainly from China. Strange boats came to the underwater forests to cut algae while off-road trucks were waiting for them on the coast. "We called the Marines to come and check on them, but they didn't come," says Samira.

Chile is among the 10 largest seaweed exporting countries in the world, harvesting some 300,000 tons of giant kelp per year. Ninety percent is exported — China is the main consumer — as dried and chopped seaweed. Roughly 10% is used in Chile to produce alginate in local industry.

According to data from the Chilean National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service (SERNAPESCA), the price soared to almost $2 a kilo in 2022, up from 50 cents per kilo in 2018. Seizures of illegally harvested giant kelp have also increased in recent years. In 2020, 467 tons were seized. In 2022, 531 tons were seized.

In theory, not just anyone can harvest giant kelp off Chile’s coast. There are a certain number of licenses (6,300) issued by SERNAPESCA. And these people have a monthly gathering quota that depends on the area (around four tons). Therefore, one of the ways in which giant kelp is laundered is by paying a seaweed gatherer who has not reached his quota or by using obsolete gathering licenses, since the registry is out of date.

There are also other forms of laundering. For example, companies receive declarations for wet algae. Once dried, they are left with a margin to "refill" with illegally collected giant kelp.

SERNAPESCA reports the number of legal cases against companies suspected of giant kelp trafficking has increased from 62 in 2020 to 146 in 2022. With the sharp increase in cases, the agency created a special program to regulate brown algae in northern Chile, but authorities say there aren’t enough agents for the long coastline that they are responsible for monitoring. The area in northern Chile where giant kelp is extracted, between Arica and Coquimbo, stretches for 932 miles – equal to the distance between Barcelona and Berlin or Panama City and Tegucigalpa.

Some companies have received several citations, such as Algas Limarí, with 15; Exportaciones M2, with 6; and Comercial y Exportaciones M2, also with 6. Paradoxically, the legal representative of Exportaciones M2, Jorge Moreno Bustos, is part of the Coquimbo brown seaweed management committee, which advises on the harvest of the giant kelp.

Another company that has been fined is Alimex S.A., of Multiexport holding, the same company that led the exploitation of algae in Peru but went bankrupt in that country.

Illegal harvesting is not the only problem. The grueling harvest takes a toll on the people who work in harsh conditions to make a modest living in an industry with very little price competition. The harvesters work under the desert sun in isolated areas, without fresh water, most of the time wet, and resist swells, which drag the giant kelp to the shore. The cycle is repeated year after year -- illegal harvesting in precarious conditions to supply global markets that pay a pittance for the forests chopped from the sea.

Giant kelp are long stems of between six and thirteen feet, joined by a holdfast that collectors call a "head.” A wet “head,” the anchor of the plant, can weigh about 20 pounds.

"Those heads are a gift from the sea, but they are also quite heavy," says Karen Valeriano, who was the last woman to join the group of gatherers in Caleta Errázuriz.

Karen is Bolivian, "a Bolivian with a sea" as she likes to say. She came to work in Antofagasta five years ago with her partner, from whom she is now separated. She has two daughters.

Before arriving in Chile, Karen had never been to the ocean. And before coming to work at Caleta Errázuriz, she did not know how to row or swim. Now she knows how to row, but she still does not know how to swim. Every morning as she kayaks across to the island, her colleagues watch her and are ready to help if the wind starts to drag her boat out to sea. "This is a free gym,” she says. “There is no coach, but you work out everything: back, arms, glutes.”

She collects giant kelp all morning and spreads it out on the beach. If she didn't spread it out, it would rot. In about three days it is dry enough to tie into bales. Then the bales are dragged to the side of the island where the boats can enter – hard work but cheaper because transporting the bales in boats from the island to the cove can be costly. The giant kelp is then sold to transporters who take it to grinders. And from the grinders it is sold to the exporters.

Companies in China convert the giant kelp into alginate, a thickening product that is used in the food industry, drugs, cosmetics, and even in mining.

"We consume alginate from the moment we get up and use shampoo in the shower to the moment we have a beer at night," says Julio Vásquez, a marine biologist and researcher at the Catholic University of the North, who has been called "the evangelist of giant kelp.” Vásquez says that few are aware of how important algae are in daily life or of all the effort behind something that seems as commonplace as the texture of a hair conditioner.

But as kelp forests are endangered, it will end up affecting not only the algae but other marine species. "Kelp forests are shelter, food, protection, and spawning areas for mollusks, fish and crustaceans. They are like buildings for humans, which, if you destroy them, you leave all the inhabitants homeless," he explains.

Vásquez believes that sustainable management works best in management areas. That is, areas given in concession to fishermen's associations where they take care of their resources, avoiding overexploitation. In Chile, these areas already exist and they have led to a lower level of overexploitation. "This way it is possible to extract algae in an orderly manner. For example, we recommend to the fishermen that they extract one giant kelp plant out of every three, to leave space for new specimens. Thus, the forest can renew itself.”

Chile should pay more attention to current extraction levels and establish how much giant kelp it wants to export, Vásquez says, especially since there are weather phenomena such as El Niño which, if they coincide with current extraction levels, "could leave us without giant kelp for a long time.”

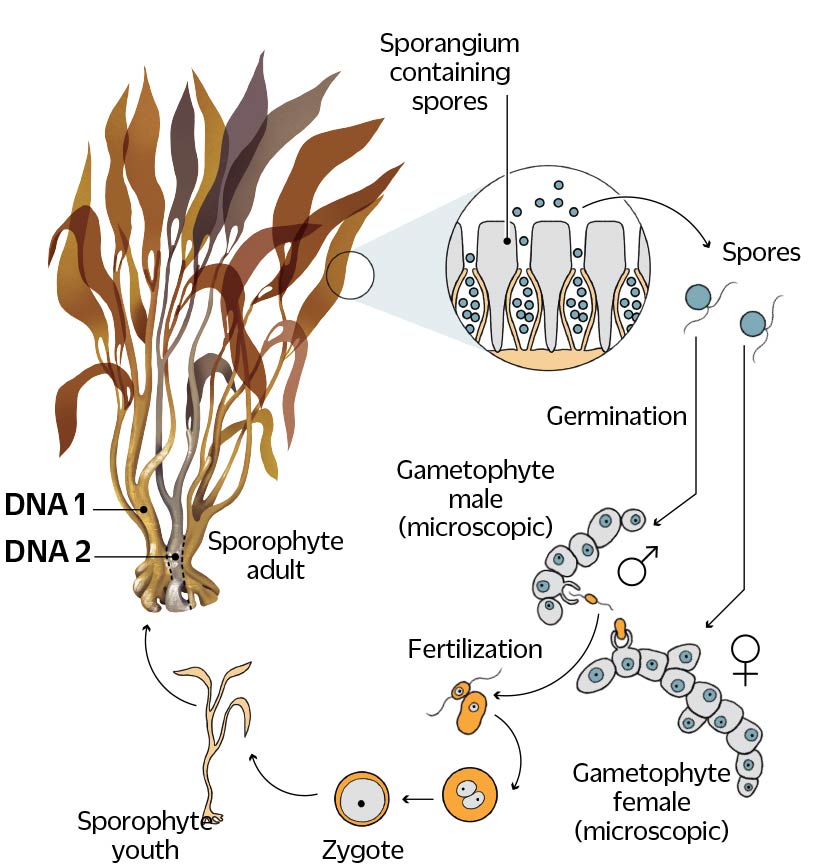

Scientists are exploring the repopulation of the ocean with brown algae to help the recovery of endangered underwater forests. The initiative works with a nature-based solution, using algae that naturally combines with other variants of the same species (chimera). This makes them more resistant to climate change and swells and they would even be able to generate higher biomass. Something like super algae.

Dr. Alejandra González, member of the faculty of Biological Sciences at the University of Chile, leads the project. After years of study and domestication of "chimera" algae cultivation, Dr. González, along with her team and four artisanal fishermen's unions, began last year to plant these algae in the management areas that belong to the unions.

They had to gain the trust of the fishermen. "It was a lengthy process because sometimes the academy gets into the communities without involving them, but in this project, they are part of it, and they have helped us a lot with their knowledge in the field to know where it is best to plant,” she said.

Chimeric algae have a higher rate of survival, growth and tolerance to increases in temperature and salinity, which makes them an option for repopulating areas highly impacted by overexploitation and may become crucial to mitigate global warming effects.

Fusion can occur between zygote cells, holdfasts, or between holdfast and zygote cells.

Planting is not easy. The giant kelp grows in high wave areas and that is precisely what makes them so desirable. "By growing in these currents, these algae produce more alginate, because alginate is what allows the elasticity that provides them with resistance to the waves," explains Dr. González.

Raúl Julio is president of a fishermen's association in Totoralillo Norte, a cove located in the Coquimbo Region of northern Chile. During the last few years, the fishermen have watched with concern as the giant kelp began to disappear and other species, such as shellfish, were also disappearing. In addition, the swells were becoming more intense.

When Dr. González's group arrived in the cove, Julio admits the fishermen were not immediately convinced. "They started introducing themselves, meeting with us, they said they wanted to combine scientific and local knowledge, and that's when we started to participate in their workshops," Julio recalls.

Four months after planting the first giant kelp plants, which were fastened to the rocks with hook-and-loop fasteners to withstand the intense waves, Julio explains that at least 50% have survived. "We want to continue working with scientists because we would like to be able to grow algae in the future. As fishermen, we also must take care of cultivating and harvesting, so that we are not just predators.”

Thousands of people attracted by a surge in seaweed exports to China have rushed to the coasts of Chile and Peru to set up new coastal villages.

Cristian Ascencio Ojeda

Roberth Orihuela Quequezana

Lynne Walker

InquireFirst

General Editor:

Iván Carrillo

Editor / Peru:

Gonzalo Torrico

Photo:

Magaly Visedo-Soriano

Cristian Ascencio Ojeda

Rodrigo Talavera Velarde

Ivan Salcedo Llerena

Web Design:

Miguel Ángel Garnica

Infographics:

Fermín García-Fabila

Translation:

Jessica Valenzuela / Translation to English

Jerusa Rodrigues / Translation to Portuguese