Two communities on opposite sides of the Ecuador-Peru border are waging their own private battles to protect their biodiverse ecosystems. The communities are only 25 miles apart yet they are unaware of their shared ideas about conservation, of efforts to create local protected areas, of careful attention to their ancestors’ traditional practices to conserve nature. They walk together, each a mirror image of the other, to save what might otherwise be lost – their forests, their pristine water and their rich biodiversity.

This is a story of the resilience of farming communities searching for sustainable alternatives in the face of scarce resources and no government support.

An invasion is looming on the border between Ecuador and Peru, an area that has witnessed four violent clashes over huge tracts of land. But this struggle, which has been going on for more than 50 years, has nothing to do with weapons, armored vehicles or uniformed troops. Rather, it involves human beings and their destructive footprint in verdant forests and crystalline rivers that are now at risk.

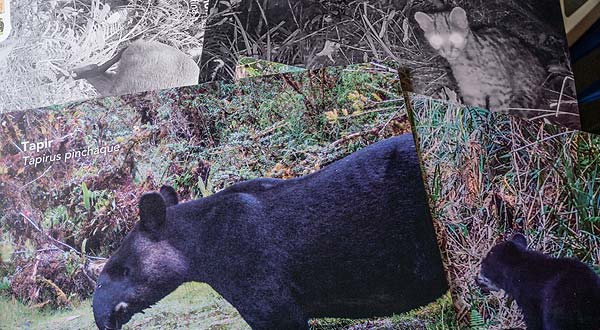

Threats to wildlife are unmistakable in the border region that extends for a little over 932 miles. Hundreds of species of flora and fauna — such as the puma and the spectacled bear — cohabit there, many of them endangered due to the loss of vegetation and pollution of water caused by deforestation, mining, hunting and other human activities.

In Ecuador, the lust for timber, oil and gold has depleted forest cover. From 2014 to 2022, the South American country lost almost 330,000 acres of native forest, according to Ecuador's Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition (MAATE), the equivalent of 186,000 soccer fields.

The destruction of native vegetation is more prevalent in the eastern Amazonian provinces, where oil wells and legal and illegal mining are also increasing, an environmental crisis shared by Ecuador and Peru.

A study by the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG) on forest loss between 2001-2020 shows the increase in deforestation in both countries: 1.5 million acres in Ecuador and 7.1 million acres in Peru.

Extractive activities have unleashed environmental and social problems. When oil companies enter the area, roads are opened and then used for other purposes as well. Over time, secondary roads are built for logging and land invasion by settlers. Viewed from the air by monitoring flights or drones, these main roads and secondary offshoots resemble the outline of the skeleton of a fish.

The rush for easy money has proved hard to resist for the inhabitants of rural towns. As mining activities have taken hold so, too, have black markets and shady businesses.

Although the authorities and institutions of both countries have implemented some protection measures and have a network of conservation areas, it has not been enough. And it has indirectly transferred conservation responsibilities to people who do not have the necessary training or resources.

But in several areas of Ecuador and Peru, there are communities that follow their ancestors' traditional practices to conserve nature. There are also populations that have rethought their presence in the territory.

That is the case of the Ecuadorian town of San Andres and the Peruvian community of Huancabamba. These towns are in different countries and their residents are unaware of their shared ideas about conservation. They are only 25 miles apart and they walk together — without knowing it — on the path of conservation, overcoming the difficulties that it represents.

In San Andres, farmers and local governments in the province of Zamora Chinchipe joined forces to seek help from nongovernmental organizations to create formal protection areas. At the same time, dozens of villagers fenced off their land to conserve the micro forests that are still standing.

In Peru, rural communities participated in the creation of private conservation areas, spaces recognized by the government for the administration and care of the environment. The community of Segunda y Cajas, in Huancabamba, organized to confront the mining activity in the territory that has cost many lives.

These are populations that, without knowing it, are looking at each other through a mirror of conservation and resilience. And today more than ever, they need to stand together in their struggle.

The elders of the communities on the border between Peru and Ecuador remember the rains that fell decades ago and draped the valleys in green. As temperatures rise and rainfall decreases, the Andean paramo ecosystem stretching from the mountain ranges of Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador to the north of Peru is key to guaranteeing the water needed by the populations and species of flora and fauna that inhabit this vast territory.

Unlike the tropical forests, the carbon stored in the paramo is not concentrated in the vegetation, but in the soil, according to information from the Ministry of the Environment (MINAM). As a result, each 2.5 acres of conserved paramo stores between 1,100 and 1,600 gallons of water per second and provides a key resource for sustaining the life on the borders of both countries.

The Andean Connectivity Corridor project, a conservation project that aims to protect almost 2.5 million acres along the Ecuador-Peru border, has been gradually developing since the signing of a presidential declaration by the two countries in 2019.

In Ecuador the corridor concept already exists, with regulations for the protection of certain ecosystems already in place. Those regulations are helping accelerate conservation efforts in Ecuador’s border region while Peru works to catch up on cross-border ecosystem protections. While the authorities work on the creation of this vast sanctuary, other ways of protecting habitats and food sources for animals are being explored in the mountains.

According to several studies, 715 species of flora and 498 species of fauna have been recorded in the area’s conservation zone. Some 168 species have been identified as endangered, such as the Ceroxylon parvifrons (palm) and the Podocarpus oleifolius (conifer), and the Andean mammal Tapirus pinchaque and the amphibian Hyloxalus sylvaticu.

The spectacled bear that is native to the region is listed as a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. It is also listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

"Working across borders implies taking into account that we are talking about two policies of different countries, where many actors participate and must establish procedures at the governmental level. Although progress is slow, there is willingness,” said Deyvis Huamán Mendoza, director of management of Peru's National Service of Natural Areas Protected by the State (SERNANP).

The Ecuador-Peru border stretches more than 932 miles, with 48 illegal access points which are used to smuggle countless items in and out of the country, according to a Peruvian intelligence report published by the newspaper El Comercio in early 2024. The illegal entry points and lack of rigorous controls at legal crossing points have been used by criminal organizations to traffic drugs, weapons and other items from which they make an illicit profit.

These are also smuggling points for wildlife trafficking, a problem that is evident when animals from Ecuador have been confiscated in Peru.

In 2017, a shipment of Galapagos tortoises was found in public transportation in Piura. In 2019, when a route used by a network of animal traffickers from the Galapagos Islands was detected, their destination was Lima, Peru, and later China. A year earlier, 123 baby tortoises were stolen from a breeding center in the Galapagos National Park. Five years later, a fisherman who was part of the network was sentenced.

In other areas of Peru there are also well-known markets where wild animals are sold, such as the Iquitos market in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon. Species from the coast, the Andean zone and abroad are traded there, according to available records.

To combat wildlife trafficking, environmental organizations are calling for improvements in border controls, the implementation of community awareness campaigns and stiffer penalties.