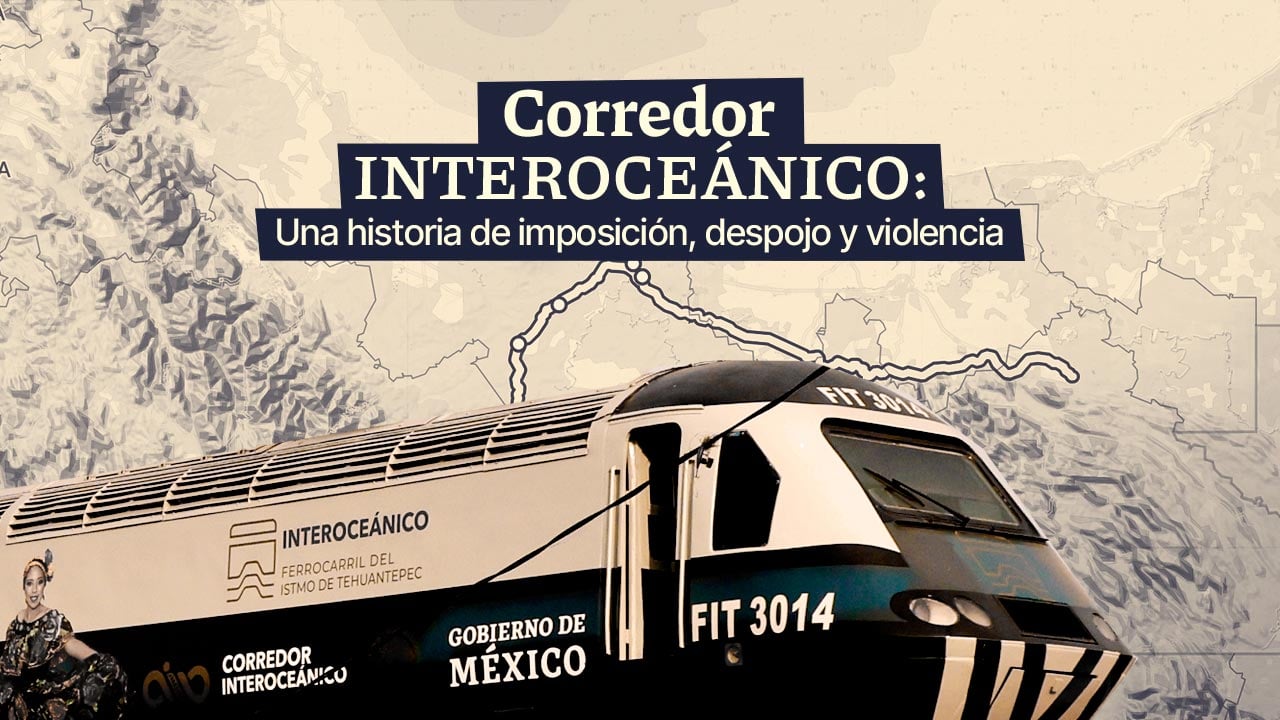

The Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec  is Mexico's alternative to the Panama Canal.

is Mexico's alternative to the Panama Canal.

Under the discourse of “development” for the Isthmus, the Mexican government will transform an area full of natural resources into an industrial landscape.

is Mexico's alternative to the Panama Canal.

is Mexico's alternative to the Panama Canal.

Under the discourse of “development” for the Isthmus, the Mexican government will transform an area full of natural resources into an industrial landscape.

By Alejandra Crail

Photographs and video Valente Rosas and Diego Prado

Photographs and video Valente Rosas and Diego Prado

This story was supported by The Pulitzer Center