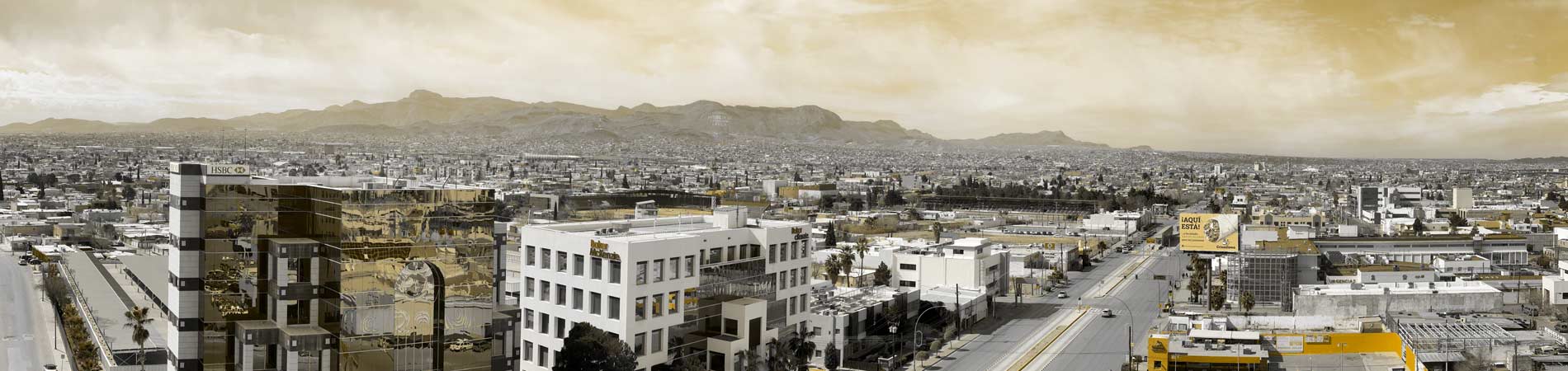

A Sea of Stories

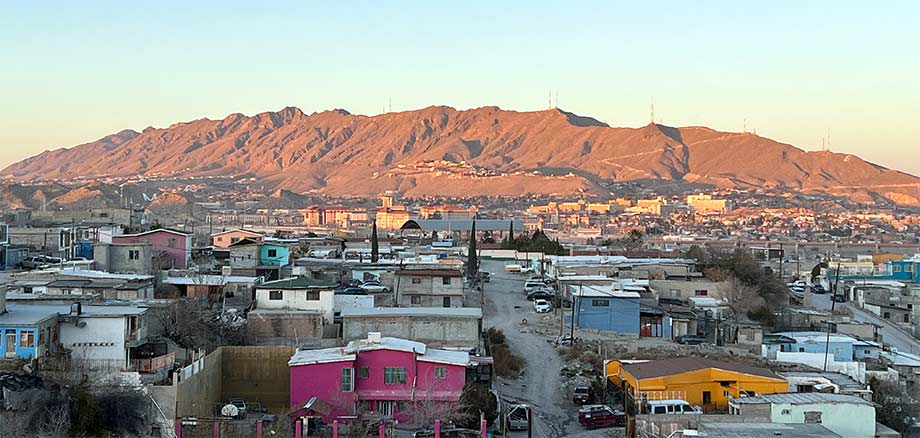

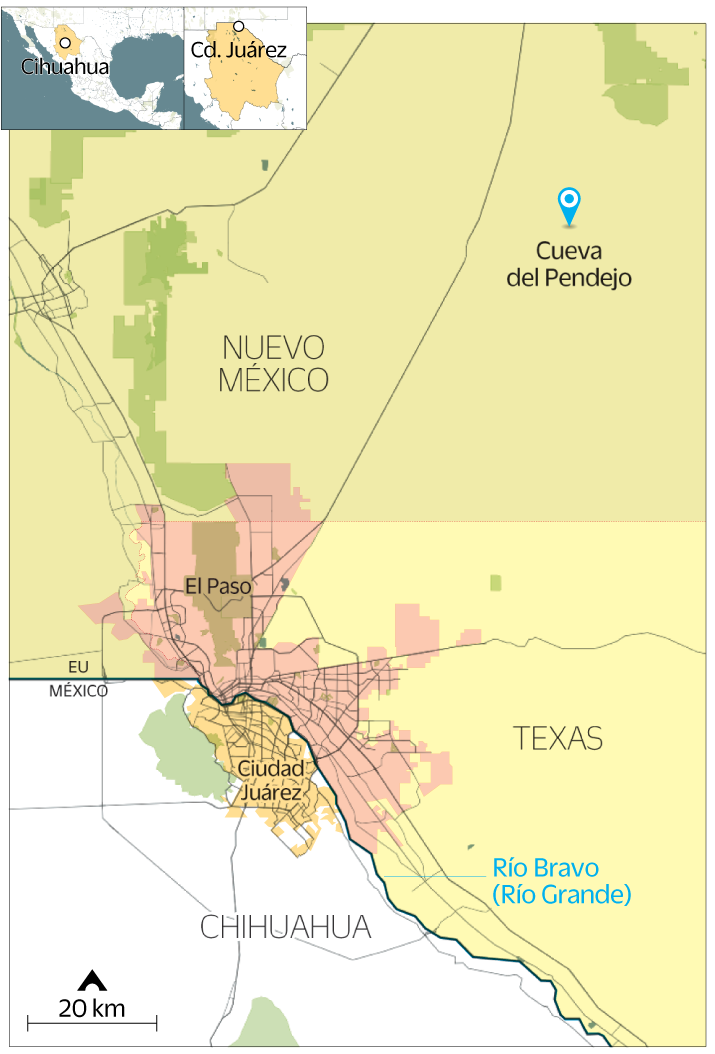

When we look at the landscape through the lens of paleontology, our imagination soars. What was life like here? Is it possible that we are walking on the ancient home of giant sharks such as Squalicorax, along with other creatures such as Pachyrhizodus and Ichthyodectes? According to Jesús Alvarado Ortega, a researcher at the Department of Paleontology of the Institute of Geology of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, this area is of utmost importance for paleontologists, as it marks the union of two marine water bodies.

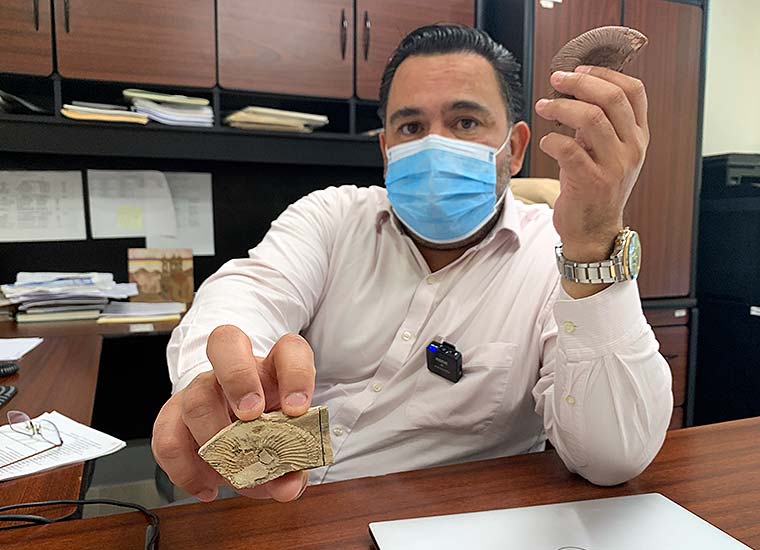

Miguel Domínguez Acosta, head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UACJ, shares this opinion and affirms that having the Sierra de Juárez in our own backyard is extremely interesting from a geological point of view, in addition to being an excellent laboratory. Domínguez has seen his students' findings, which range from wood and oyster fossils to dinosaur footprints.

Miguel Domínguez Acosta, head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering of the UACJ. Photo: Juan Antonio Castillo

Miguel Domínguez Acosta, head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering of the UACJ. Photo: Juan Antonio Castillo A shark tooth found by Universidad Autónoma Ciudad Juárez students in Sierra de Juárez is on display in the university’s geology laboratory. Photo: Juan Antonio Castillo

A shark tooth found by Universidad Autónoma Ciudad Juárez students in Sierra de Juárez is on display in the university’s geology laboratory. Photo: Juan Antonio Castillo

The UACJ professor says that his students were on an expedition in the Sierra de Juárez when they found a shark tooth embedded in a loose rock. Unfortunately, since the rock was in their path, the discovery lacks scientific substantiation. Today, the piece is on display at the UACJ Geology Laboratory, which holds about 3,000 specimens: rocks, minerals, and fossils from over 100 million years ago.

Each fossil tells a story that belongs to a bygone scenario, according to geophysicist Óscar Sotero Dena Ornelas, a researcher at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez. With 4.6 billion years of existence, our planet has experienced changes in its tectonics and the formation of continents and seas throughout time.

As we step out into the vast desert known as the Great Chihuahuan Desert today, we must remember that in the Jurassic period, 201 million years ago, this land was a shallow tropical sea known as the Tethys Sea. According to Dr. Jesús Alvarado Ortega, this sea, whose name honors the Greek goddess of the sea, Tethys, formed as a large bay in the Triassic period and eventually expanded to the west, reaching North American territory and opening into the ancient Pacific Ocean.

To complete the picture of what this valley was like in the remote past, we must listen to the words of Thomas Schiller, an expert in collecting and documenting vertebrate fossils from the Cretaceous-Paleogene period. During this time, the region of south Texas and northern Mexico experienced geological changes that defined the landscape as we know it today.

Schiller, a professor at Sul Ross State University in Texas, explains that after the movements of ancient tectonic plates and the formation of several basins in the region during the early Cretaceous, the Western Interior Seaway developed. This marine water body, which expanded and contracted over hundreds of thousands of years, covered part of the American continent, from southern Mexico to the central-northeastern United States, Canada and the Southern Arctic.

In northern Mexico, between Coahuila and Chihuahua, as well as in the Big Bend area of Texas, unique populations of animals and plants have been discovered that could only have existed due to the climatic conditions of the region. Among the fossils found in this area are snails, shelled squids, and numerous species of marine reptiles, such as the Mosasaurus, one of the top predators of the time, with a length of between 26 and 49 feet, a weight of up to 15 tons and a swimming speed of up to 31 miles per hour.

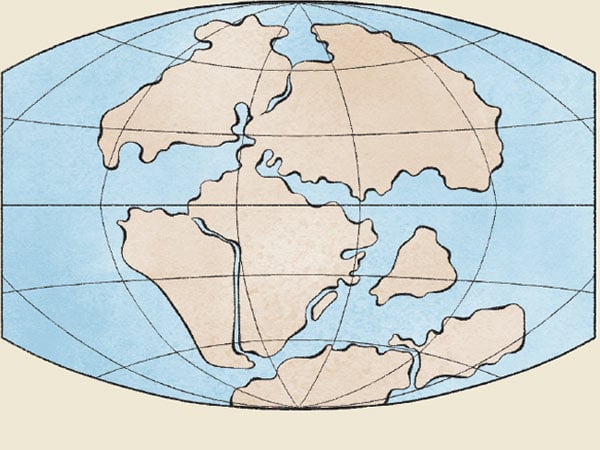

Alvarado reminds us that, in order to understand our present, it is necessary to understand our past, and with this in mind, the analysis of life adapted to geography has revealed a peculiar history. During the beginning of the Jurassic period, there was a realignment of the tectonic plates that caused an increase in water levels in the supercontinent called Pangea. The continents separated, the oceans entered the scene, and the Atlantic Ocean was formed. At that time, Central America did not yet exist, and the tropical part was a narrow corridor, which connected the Gulf of Mexico to the Western Interior Seaway.

This separation, Alvarado explains, occurred when the ancient continent split from East to West, separating Europe and North America, and also separating Africa from South America, thus forming the distribution of the continents as we know them today.

Among the most notable inhabitants of this region was the Xiphactinus, a prehistoric fish of ferocious appearance, with large teeth and powerful jaws. In addition, fossils of direct ancestors of sharks have been discovered in gigantic proportions, such as Squalicorax. According to the studies carried out by the UNAM paleontologist, these sharks and marine reptiles were distributed further North and occupied U.S. territory, while on the Mexican side, there were similar organisms that developed in a more tropical zone, with a closer relationship to European forms.

As some organisms saw their diversity reduced, other groups began to flourish and established direct links with modern fauna. We can say that, during the Cretaceous period, the faunal composition that still prevails today was produced. However, this period came to an end after 65 million years, marked by a mass extinction event caused by the impact of the Chicxulub meteorite in present-day Yucatan, in Southeastern Mexico.

This event caused massive mortality that was recorded in fossils found in the rocks. Many older organisms disappeared, and the rocks formed after this event contain fossils of a different nature. Dinosaurs and other ancient representatives of marine life, such as the famous Xiphactinus of Kansas, disappeared forever, but vestiges are still found.

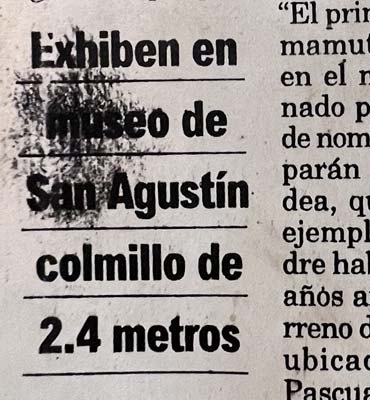

Origin of Camels: A Find in America

El Paso is one of the few cities in the world where fossils and rocks from all seven periods of the Paleozoic era can be found in one place -- the Centennial Museum. Daniel Carey-Whalen, the museum director, says it is common for locals to find seashells and other fossils in their backyards.

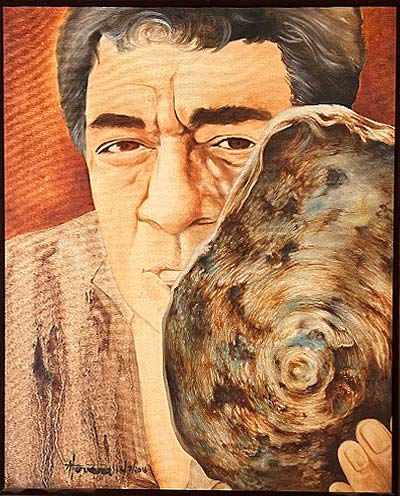

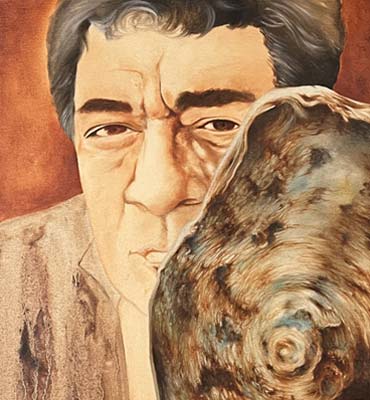

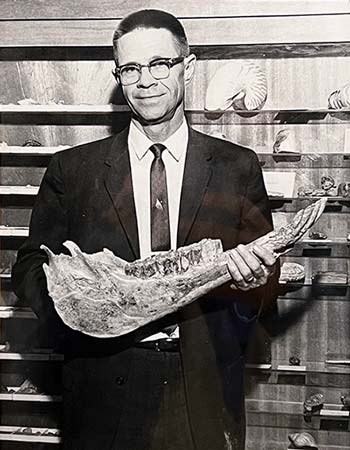

Dr. William Strain, fundador del museo Centennial de UTEP, muestra un fósil de quijada de camello que se encuentra hoy en día en exhibición en el mismo museo. Photo: UTEP Centennial Museum

Dr. William Strain, fundador del museo Centennial de UTEP, muestra un fósil de quijada de camello que se encuentra hoy en día en exhibición en el mismo museo. Photo: UTEP Centennial MuseumAlthough the museum focuses on the life and culture of the Great Chihuahuan Desert, its paleontology exhibition room displays fossils from various geological eras. Among them are giant ammonites, shells, fish, plants and remains of saber-toothed cats and mammoths.

One of the most significant finds of the Centennial Museum's founder and first curator, Dr. William Strain, was a fossilized camel jawbone, discovered at the top of Franklin Mountain in the mid-20th century. Later, he also managed to recover fossilized bones of horses, proving the presence of these species in America long before they appeared in the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

"It is believed that horses and other species migrated northward, then crossed the Bering Strait and that is why these species disappeared from our continent," explains the museum director. The geography of the region has been, for millions of years, a key piece for the migration of various species.

"Let's Celebrate Our Mountains":

The Importance of Our Geological Environment

Oscar Sotero Dena, Ph.D. in Geological Sciences and researcher at the UACJ, emphasizes the need to divulge knowledge and appreciation of our geological environment.

Oscar Sotero Dena, a Ph.D. in geological sciences and researcher at the Universidad Autónoma Ciudad Juárez, says the geological discoveries have no border and should be appreciated and enjoyed by residents of the region. Photo: Juan Antonio Castillo

Oscar Sotero Dena, a Ph.D. in geological sciences and researcher at the Universidad Autónoma Ciudad Juárez, says the geological discoveries have no border and should be appreciated and enjoyed by residents of the region. Photo: Juan Antonio Castillo

As an example, he mentions the city of Albuquerque, where the characteristic "Sandia Peak" has been transformed into a geopark that attracts local residents with hiking, cable cars, restaurants and scenic viewpoints. "All of that encourages people in the region to come to its mountains," he says.

UTEP also holds an annual "We Celebrate Our Mountains," an initiative that includes visits to the Sierra de Juárez, Samalayuca, Sierra del Presidio, and Franklin Mountain. "All of these geological expressions have no borders and we should celebrate that they are closer to us than we are to them," he adds.

Sotero Dena proposes that Sierra de Juárez, considered the most important geological heritage and one of the reasons why the UACJ created the Geosciences program, be recognized as a geological park, a space for walking, hiking and allowing biologists to study the regional flora and evaluate its potential for aquifer recharge.

The same is proposed for Sierra de Guadalupe, where there is a gigantic, "marvelous" reef outcrop, which shows the ecosystem conditions that prevailed, such as temperature, as well as the depth and salinity of the oceans that were present when the marine muds that gave way to these rocks were deposited to later form the rocks that now outcrop in the middle of the continent.

The researcher emphasizes that the city needs more recreational options that are not necessarily associated with alcohol consumption. However, he recognizes the challenges the region faces: "It is now complicated to walk through the highlands, both because of the orographic features and the presence of people with antisocial behavior". His proposal advocates the creation of safe trails that facilitate access and promote more respect and appreciation for our geological heritage.